This article was originally published on Binpress

In computer science, agent-based models are used to assess the effects of autonomous agents (i.e. individuals, groups or objects) on an overall system. They're very powerful analytical tools that can be used in situations where experiments aren't feasible or are very expensive to conduct. These models have a wide range of applications in the social sciences, computer science, economics and business.

In this piece, I'll introduce you to the power of agent-based models when used to understand complex phenomenons. To do this, we'll use some Python, a social science case study and the Schelling model.

1. The case study

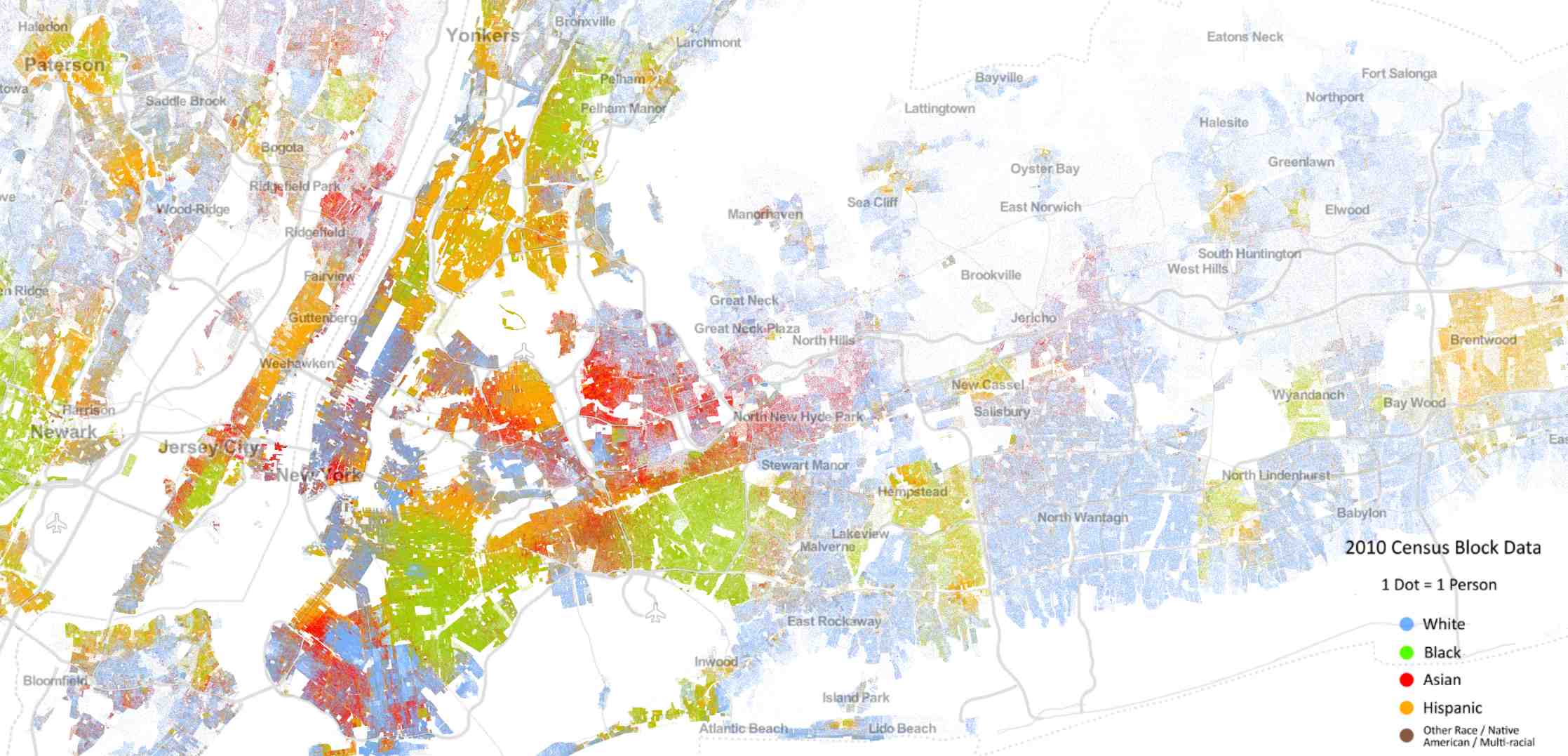

If you look at the racial distribution of multi-ethnic cities, you'll be astonished by the incredible racial segregation. For example, the New York City map below represents data from the 2010 US Census color-coded by race. You can clearly see the racial segregation.

Many would conclude from such phenomena that people are intolerant, and don't want to live next to people that are different from them. A deeper look, however, might provide some nuance. In the 70's, Thomas Schelling, the 2005 Economics Nobel Prize winner, was interested in this subject and built an agent-based model called the "Schelling segregation model" for explaining this phenomenon. With a very simple model, Schelling could show that what we see at the macro level may not in fact represent what's going down in the micro level.

We'll run a few simulations using the Schelling model to get a deeper understanding of the segregation phenomena.

2. Schelling Segregation Model: Setting and Definitions

Agent-based models need three parameters: 1) Agents, 2) Behavior (rules) and 3) Metrics at the aggregated level. In the Schelling model, the agents are the people living in the city, the behavior is the house moving based on the similarity ratio and the metrics at the aggregated level is the similarity ratio.

Let n be the number of races living in a city. We represent each race by a unique color and we represent the city by a grid where each cell represents a house. A house can be either empty or full. A full house can have have only one person living in it. If the house is empty, we color it in white. If the house is full, we color it by the color of the person living in it. We define the neighbors of a person to be the people living in the adjacent houses (Up, Bottom, Left, Right, Up-Left, Up-Right, Bottom-Left, Bottom-Right).

Schelling's goal was to test what would happen if people had a small preference that their neighbors be of the same color (or even preference for some diversity). If the ratio of neighbors of the same race is above a certain threshold (that we call Similarity Threshold), we say that the person is satisfied. If not, we say that the person is unsatisfied.

The Schelling simulation goes as follows. We start by randomly putting people in the city and we leave some houses empty. For each person living in the city, we check if he/she is satisfied. If satisfied, we don't do anything. If not, we move the person to an empty house. We run this simulation for a few iterations, and we check the final distribution of the people.

3. Python Implementation of Schelling Model

Back in the 70s, Schelling used pennies and nickels on a piece of paper for his simulation. We'll use Python for building the same simulation.

We start by importing the necessary libraries for running the simulations. All libraries except Matplotlib are installed by default in Python.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import itertools

import random

import copy

Next, we define a class called Schelling. This class takes 6 parameters: the width and height of the city, the ratio of empty houses in the city, the similarity threshold, the number of iterations and the number of races. We define 4 methods within the Schelling class: populate, is_unsatisfied, update, move_to_empty, and plot.

class Schelling:

def __init__(self, width, height, empty_ratio, similarity_threshold, n_iterations, races = 2):

self.width = width

self.height = height

self.races = races

self.empty_ratio = empty_ratio

self.similarity_threshold = similarity_threshold

self.n_iterations = n_iterations

self.empty_houses = []

self.agents = {}

def populate(self):

....

def is_unsatisfied(self, x, y):

....

def update(self):

....

def move_to_empty(self, x, y):

....

def plot(self):

....

The populate method is used at the beginning of the simulation. This method distributes randomly people in the grid.

def populate(self):

self.all_houses = list(itertools.product(range(self.width),range(self.height)))

random.shuffle(self.all_houses)

self.n_empty = int( self.empty_ratio * len(self.all_houses) )

self.empty_houses = self.all_houses[:self.n_empty]

self.remaining_houses = self.all_houses[self.n_empty:]

houses_by_race = [self.remaining_houses[i::self.races] for i in range(self.races)]

for i in range(self.races):

#create agents for each race

self.agents = dict(

self.agents.items() +

dict(zip(houses_by_race[i], [i+1]*len(houses_by_race[i]))).items()

)

The is_unsatisfied method takes as arguments the (x, y) coordinates of a house, check the ratio of neighbors of similar color, and returns True if the ratio is above the happiness threshold, otherwise it returns False.

def is_unsatisfied(self, x, y):

race = self.agents[(x,y)]

count_similar = 0

count_different = 0

if x > 0 and y > 0 and (x-1, y-1) not in self.empty_houses:

if self.agents[(x-1, y-1)] == race:

count_similar += 1

else:

count_different += 1

if y > 0 and (x,y-1) not in self.empty_houses:

if self.agents[(x,y-1)] == race:

count_similar += 1

else:

count_different += 1

if x < (self.width-1) and y > 0 and (x+1,y-1) not in self.empty_houses:

if self.agents[(x+1,y-1)] == race:

count_similar += 1

else:

count_different += 1

if x > 0 and (x-1,y) not in self.empty_houses:

if self.agents[(x-1,y)] == race:

count_similar += 1

else:

count_different += 1

if x < (self.width-1) and (x+1,y) not in self.empty_houses:

if self.agents[(x+1,y)] == race:

count_similar += 1

else:

count_different += 1

if x > 0 and y < (self.height-1) and (x-1,y+1) not in self.empty_houses:

if self.agents[(x-1,y+1)] == race:

count_similar += 1

else:

count_different += 1

if x > 0 and y < (self.height-1) and (x,y+1) not in self.empty_houses:

if self.agents[(x,y+1)] == race:

count_similar += 1

else:

count_different += 1

if x < (self.width-1) and y < (self.height-1) and (x+1,y+1) not in self.empty_houses:

if self.agents[(x+1,y+1)] == race:

count_similar += 1

else:

count_different += 1

if (count_similar+count_different) == 0:

return False

else:

return float(count_similar)/(count_similar+count_different) < self.happy_threshold

The update method checks if each person in the grid is unsatisfied, if yes it assigns the person to a randomly chosen empty house. It runs this process n_iterations times.

def update(self):

for i in range(self.n_iterations):

self.old_agents = copy.deepcopy(self.agents)

n_changes = 0

for agent in self.old_agents:

if self.is_unhappy(agent[0], agent[1]):

agent_race = self.agents[agent]

empty_house = random.choice(self.empty_houses)

self.agents[empty_house] = agent_race

del self.agents[agent]

self.empty_houses.remove(empty_house)

self.empty_houses.append(agent)

n_changes += 1

print n_changes

if n_changes == 0:

break

The move_to_empty method takes as arguments the (x, y) coordinates of a house, and moves the person living in the (x, y) house to an empty house. This method is called within the update method to move the unsatisfied people to empty houses.

def move_to_empty(self, x, y):

race = self.agents[(x,y)]

empty_house = random.choice(self.empty_houses)

self.updated_agents[empty_house] = race

del self.updated_agents[(x, y)]

self.empty_houses.remove(empty_house)

self.empty_houses.append((x, y))

The plot method is used to draw the whole city and people living in the city. We can call this method at anytime to check the distribution of people in the city. This method takes 2 arguments title, and file_name.

def plot(self, title, file_name):

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

#If you want to run the simulation with more than 7 colors, you should set agent_colors accordingly

agent_colors = {1:'b', 2:'r', 3:'g', 4:'c', 5:'m', 6:'y', 7:'k'}

for agent in self.agents:

ax.scatter(agent[0]+0.5, agent[1]+0.5, color=agent_colors[self.agents[agent]])

ax.set_title(title, fontsize=10, fontweight='bold')

ax.set_xlim([0, self.width])

ax.set_ylim([0, self.height])

ax.set_xticks([])

ax.set_yticks([])

plt.savefig(file_name)

4. Simulations

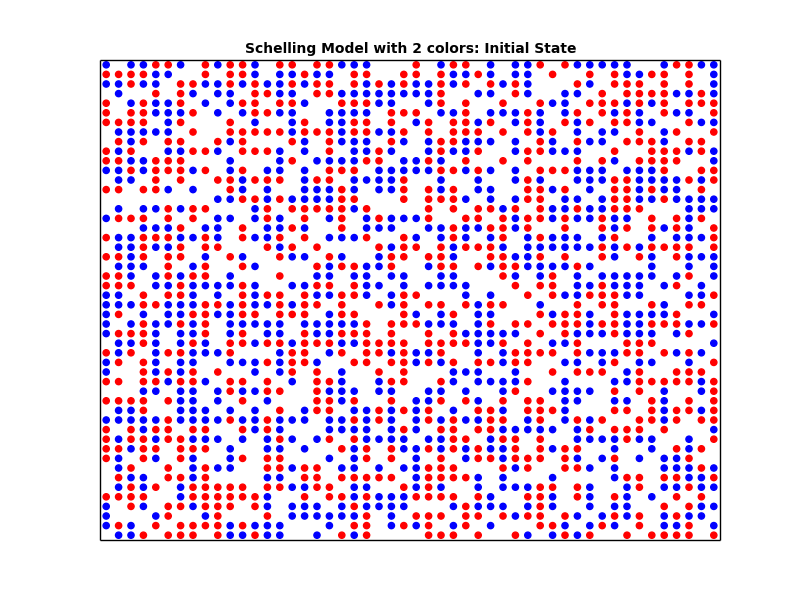

Now that we have our implementation of the Schelling class, we can run different simulations and plot the results. we will build 3 simulations with the following characteristics:

- width = 50, and height = 50 (2500 houses)

- 30% of empty houses

- Similarity Threshold = 30% (for Simulation 1), Similarity Threshold = 50% (for Simulation 2), and Similarity Threshold = 80% (for Simulation 3)

- Maximum number of iterations = 500

- Number of races = 2

We start by creating and populating the cities.

schelling_1 = Schelling(50, 50, 0.3, 0.3, 500, 2)

schelling_1.populate()

schelling_2 = Schelling(50, 50, 0.3, 0.5, 500, 2)

schelling_2.populate()

schelling_3 = Schelling(50, 50, 0.3, 0.8, 500, 2)

schelling_3.populate()

Next, we plot the city at the initial phase. Note that the Similarity threshold has no effect on the initial state of the city.

schelling_1_1.plot('Schelling Model with 2 colors: Initial State', 'schelling_2_initial.png')

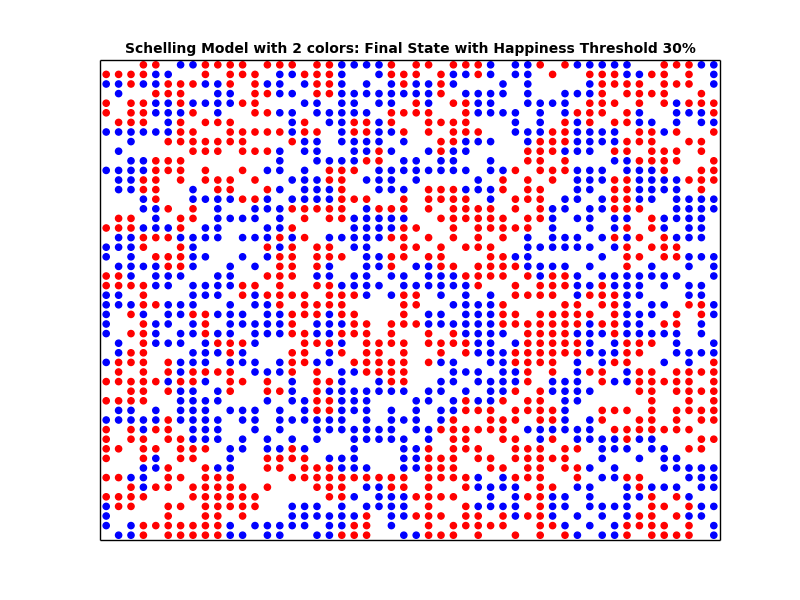

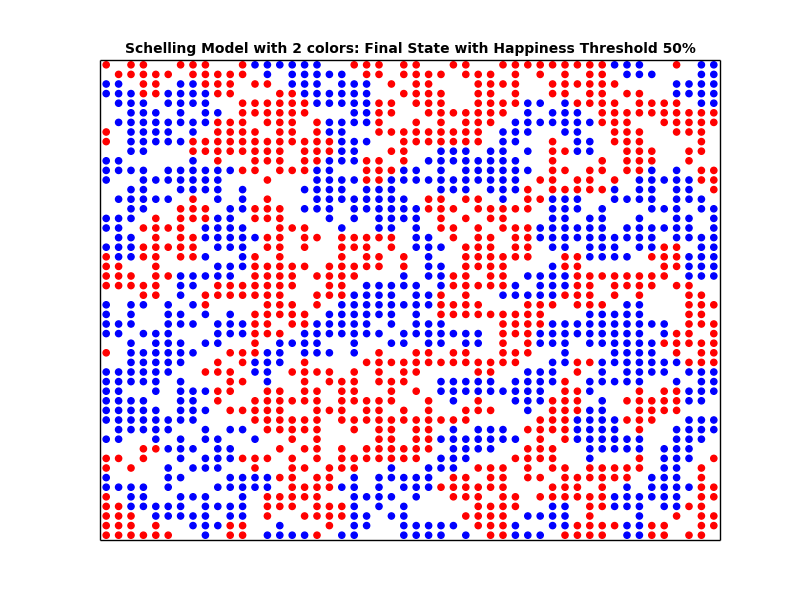

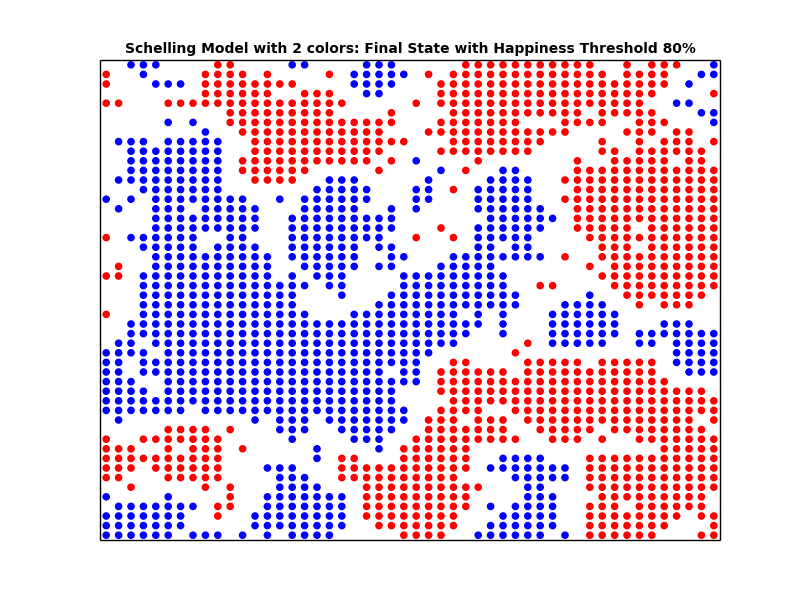

Next, we run the update method, and we plot the final distribution for both Similarity thresholds.

schelling_1.update()

schelling_2.update()

schelling_3.update()

schelling_1.plot('Schelling Model with 2 colors: Final State with Similarity Threshold 30%', 'schelling_2_30_final.png')

schelling_2.plot('Schelling Model with 2 colors: Final State with Similarity Threshold 50%', 'schelling_2_50_final.png')

schelling_3.plot('Schelling Model with 2 colors: Final State with Similarity Threshold 80%', 'schelling_2_80_final.png')

Looking at the plots above, we can see that the higher the similarity threshold, the more segregated the city becomes. Furthermore, we can see that even with a small similarity threshold, we get segregated cities. In other words, even if the people are very tolerant (i.e. having a small Similarity threshold), we end up with segregation. We can conclude that what we see at the macro level may not in fact represent what's going down in the micro level.

5. Measuring Segregation

In the simulation above, we used visual representations to confirm the segregation. However, we don't have any quantitative measure for calculating segregation. We will define this measure in this section, and we will run a few simulations to check the relationship between the happiness threshold and the segregation level.

First we will add a method to the Schelling class called calculate_similarity. This method returns the calculate the similarity ratio for each agent and returns the mean similarity ratio. We will use the mean similarity ratio as a measure of segregation.

def calculate_similarity(self):

similarity = []

for agent in self.agents:

count_similar = 0

count_different = 0

x = agent[0]

y = agent[1]

race = self.agents[(x,y)]

if x > 0 and y > 0 and (x-1, y-1) not in self.empty_houses:

if self.agents[(x-1, y-1)] == race:

count_similar += 1

else:

count_different += 1

if y > 0 and (x,y-1) not in self.empty_houses:

if self.agents[(x,y-1)] == race:

count_similar += 1

else:

count_different += 1

if x < (self.width-1) and y > 0 and (x+1,y-1) not in self.empty_houses:

if self.agents[(x+1,y-1)] == race:

count_similar += 1

else:

count_different += 1

if x > 0 and (x-1,y) not in self.empty_houses:

if self.agents[(x-1,y)] == race:

count_similar += 1

else:

count_different += 1

if x < (self.width-1) and (x+1,y) not in self.empty_houses:

if self.agents[(x+1,y)] == race:

count_similar += 1

else:

count_different += 1

if x > 0 and y < (self.height-1) and (x-1,y+1) not in self.empty_houses:

if self.agents[(x-1,y+1)] == race:

count_similar += 1

else:

count_different += 1

if x > 0 and y < (self.height-1) and (x,y+1) not in self.empty_houses:

if self.agents[(x,y+1)] == race:

count_similar += 1

else:

count_different += 1

if x < (self.width-1) and y < (self.height-1) and (x+1,y+1) not in self.empty_houses:

if self.agents[(x+1,y+1)] == race:

count_similar += 1

else:

count_different += 1

try:

similarity.append(float(count_similar)/(count_similar+count_different))

except:

similarity.append(1)

return sum(similarity)/len(similarity)

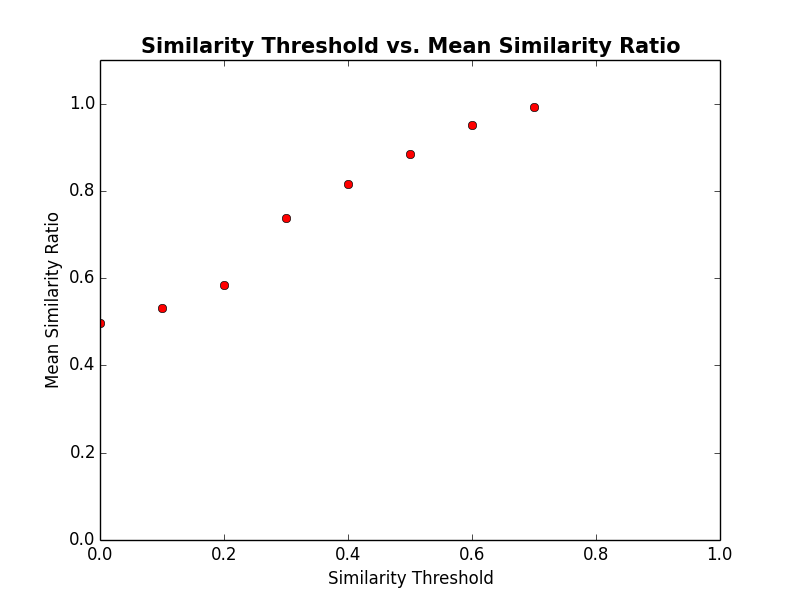

Next, we will calculate the mean similarity ratio for different similarity thresholds, and we will plot the relationship between the similarity threshold and the similarity ratio.

similarity_threshold_ratio = {}

for i in [0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7]:

schelling = Schelling(50, 50, 0.3, i, 500, 2)

schelling.populate()

schelling.update()

similarity_threshold_ratio[i] = schelling.calculate_similarity()

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

plt.plot(similarity_threshold_ratio.keys(), similarity_threshold_ratio.values(), 'ro')

ax.set_title('Similarity Threshold vs. Mean Similarity Ratio', fontsize=15, fontweight='bold')

ax.set_xlim([0, 1])

ax.set_ylim([0, 1.1])

ax.set_xlabel("Similarity Threshold")

ax.set_ylabel("Mean Similarity Ratio")

plt.savefig('schelling_segregation_measure.png')

You can see from the plot above that for very small similarity thresholds, we get very high segregation (defined by the mean similarity ratio). For example, for a similarity threshold of 0.3, we got a mean similarity ratio of 0.75. We could confirm quantitatively that what we see at the macro level may not in fact represent what's going down in the micro level.

6. Wrap-up

In this article, we've introduced one example of agent-based models called, the Schelling segregation model, and we implemented it in Python. This very simple model helped us understand a very complex phenomena, namely segregation in multi-ethnics cities. We could show that a very high segregation level in these cities doesn't necessarily translate into intolerance at the individual level.

All source code from this post can be found in this github repository.

References

https://www.coursera.org/course/modelthinking

Go Top Source:

Source: